A “sonogram” results from collecting echoes bouncing off an object and mapping tiny differences in the time it takes to receive the echoes. This “map” forms a picture; many pregnant women have this done to themselves and most everyone has seen a sonogram of an unborn child.

This is essentially what a bat does in its brain when it listens for echoes of it’s calls!

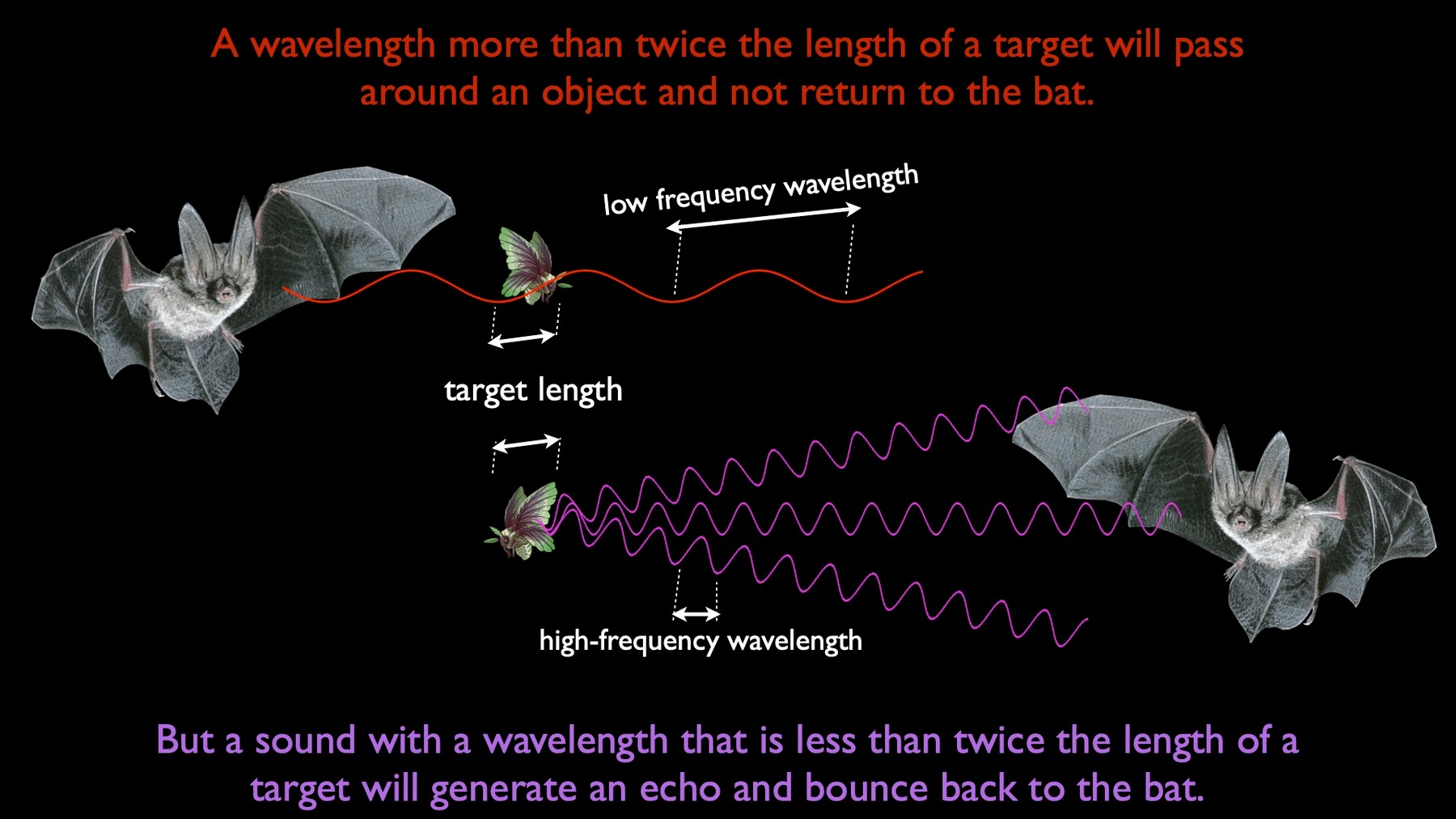

Sound waves oscillate between positive and negative values over time. How fast the waves move is the "frequency". We have to measure bat calls in "kilohertz" (kHz), meaning 1000 cycles per second.

People can hear sound up to about 20 kHz. Most bats start talking above 20 kHz, so generally we can't hear them without special microphones. Many bats are very loud - over 100 dB, which is like a smoke alarm. Imagine the night sky filled with animals this loud! Insects can hear bats though, so there is constantly a dramatic hunt & struggle in the dark anywhere there are bats.

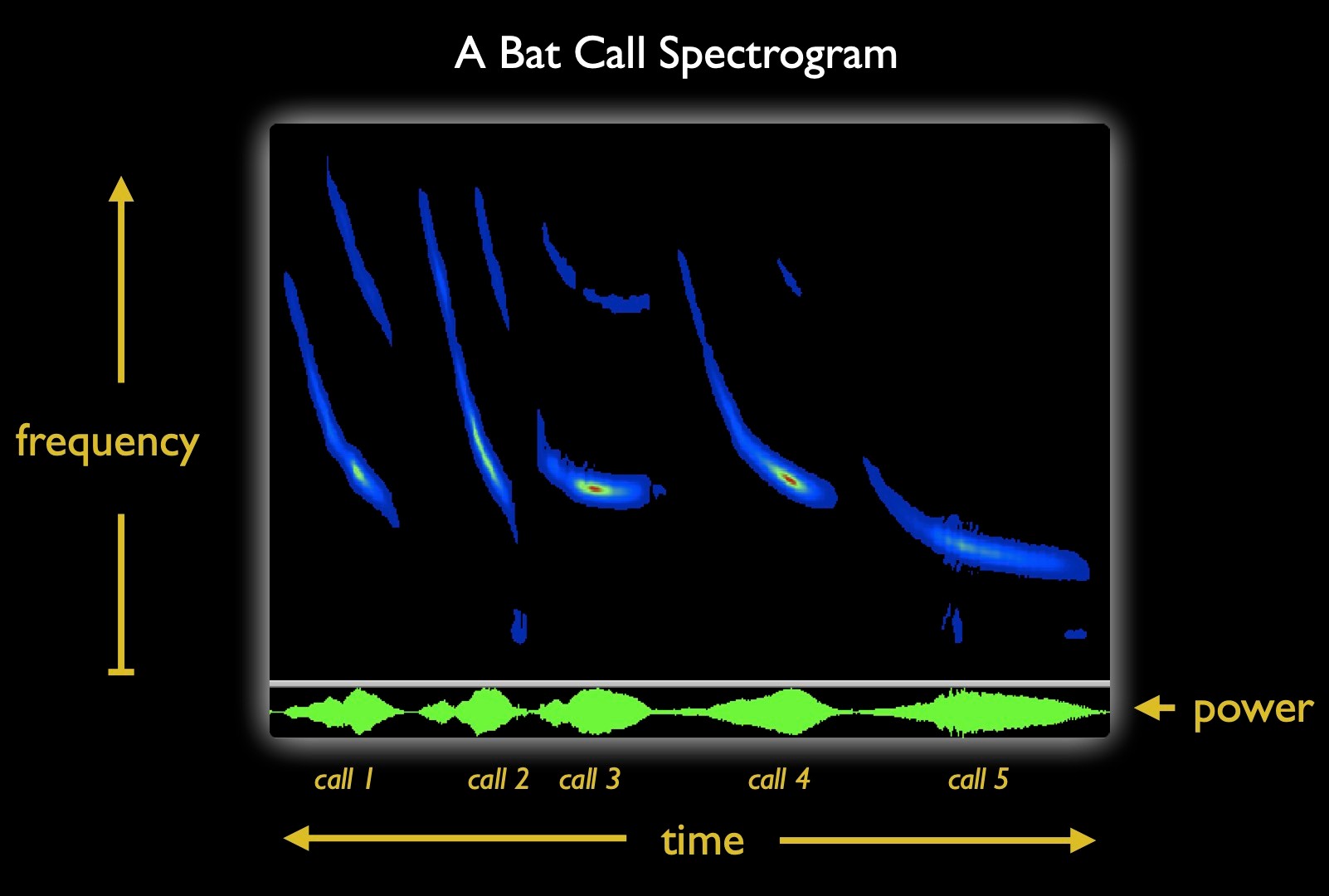

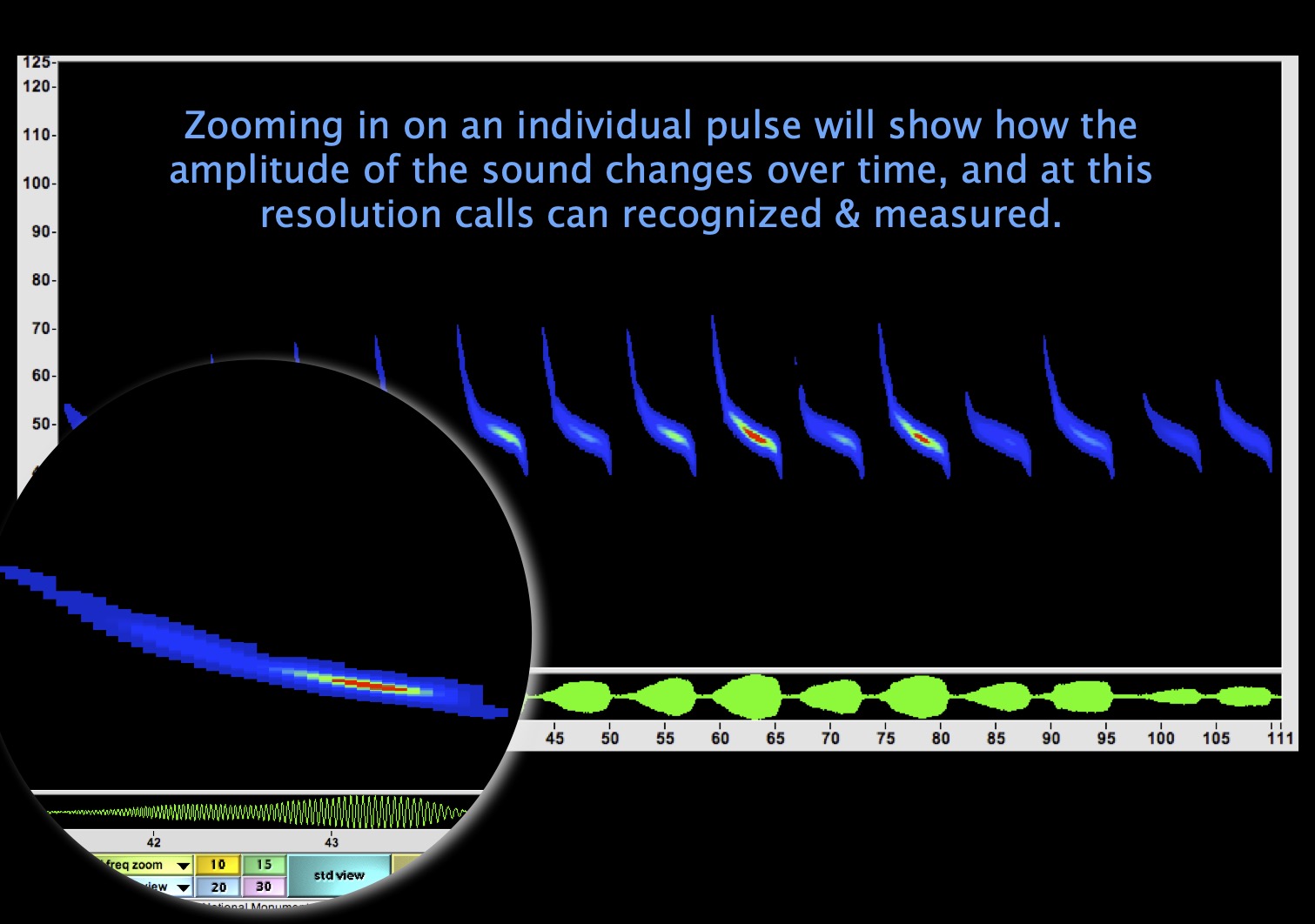

A “spectrogram” recording of five bat calls displays the frequency over time. Mapping this begins to show us the "shape" of the individual bat calls. The intensity of the calls appears as “hot spots” which correspond to the loudest portion of the call.

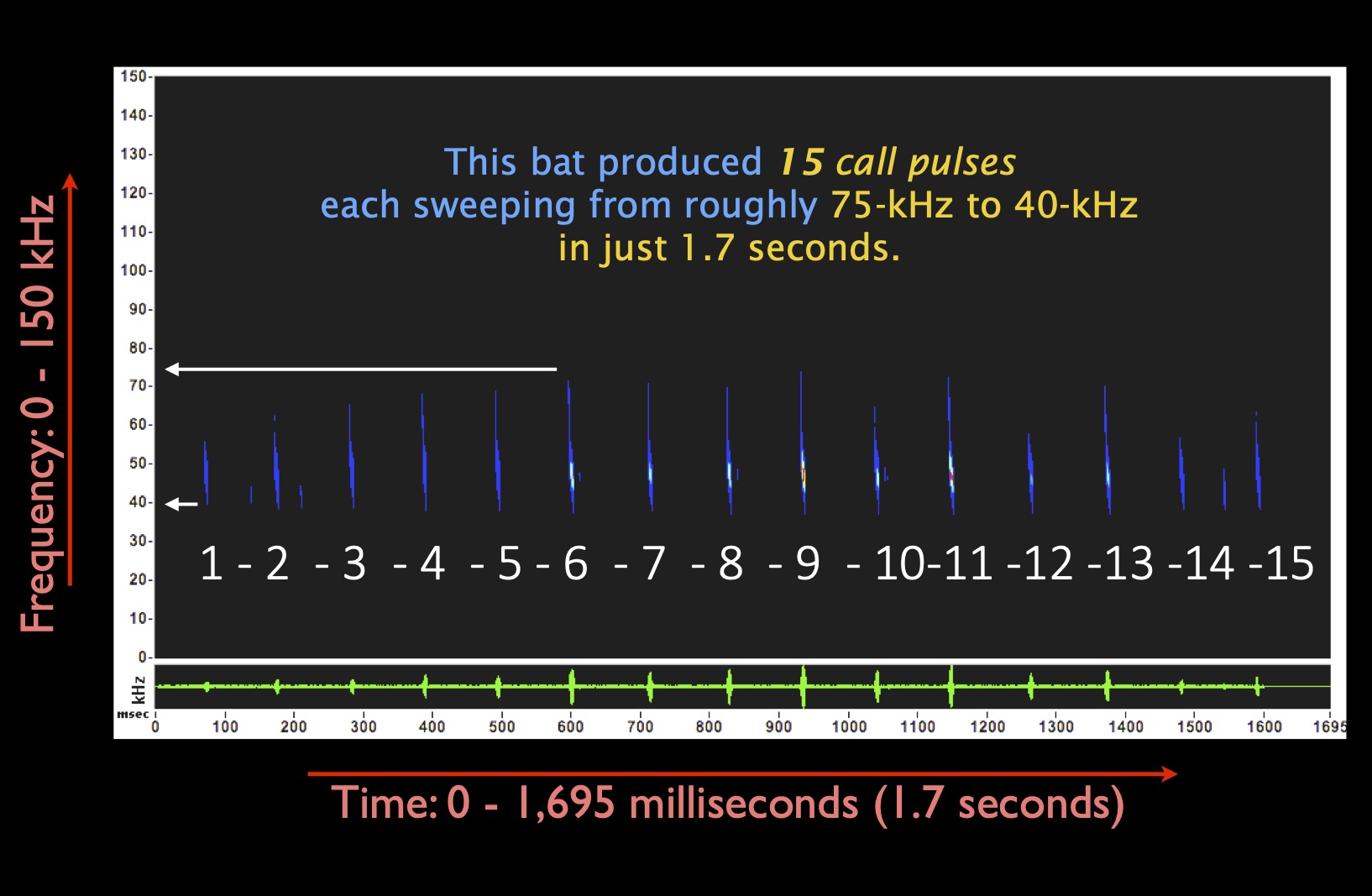

This bat has produced 15 discrete echolocation call pulses sweeping from roughly 80-kHz down to 40-kHz in just 1.7 seconds. But measurements in “kilohertz” and “milliseconds” are beyond what we relatively “sound-impaired” humans can appreciate.

And our ears lose their sensitivity when the length of a sound is less than 100ms . . . most bat calls are only 2-20 ms in duration.

So, even when we can transform bat sounds into sound pictures, we can’t view them with a fine enough resolution to form pictures with obvious characteristics.

The typical short-duration bat sounds are separated by relatively large periods of silence; so we can remove the silence and re-draw the bat calls with increased resolution. Now we can visualize many of the metrics used to measure bat calls, and this is the first step in learning how to identify bats from their echolocation recordings.

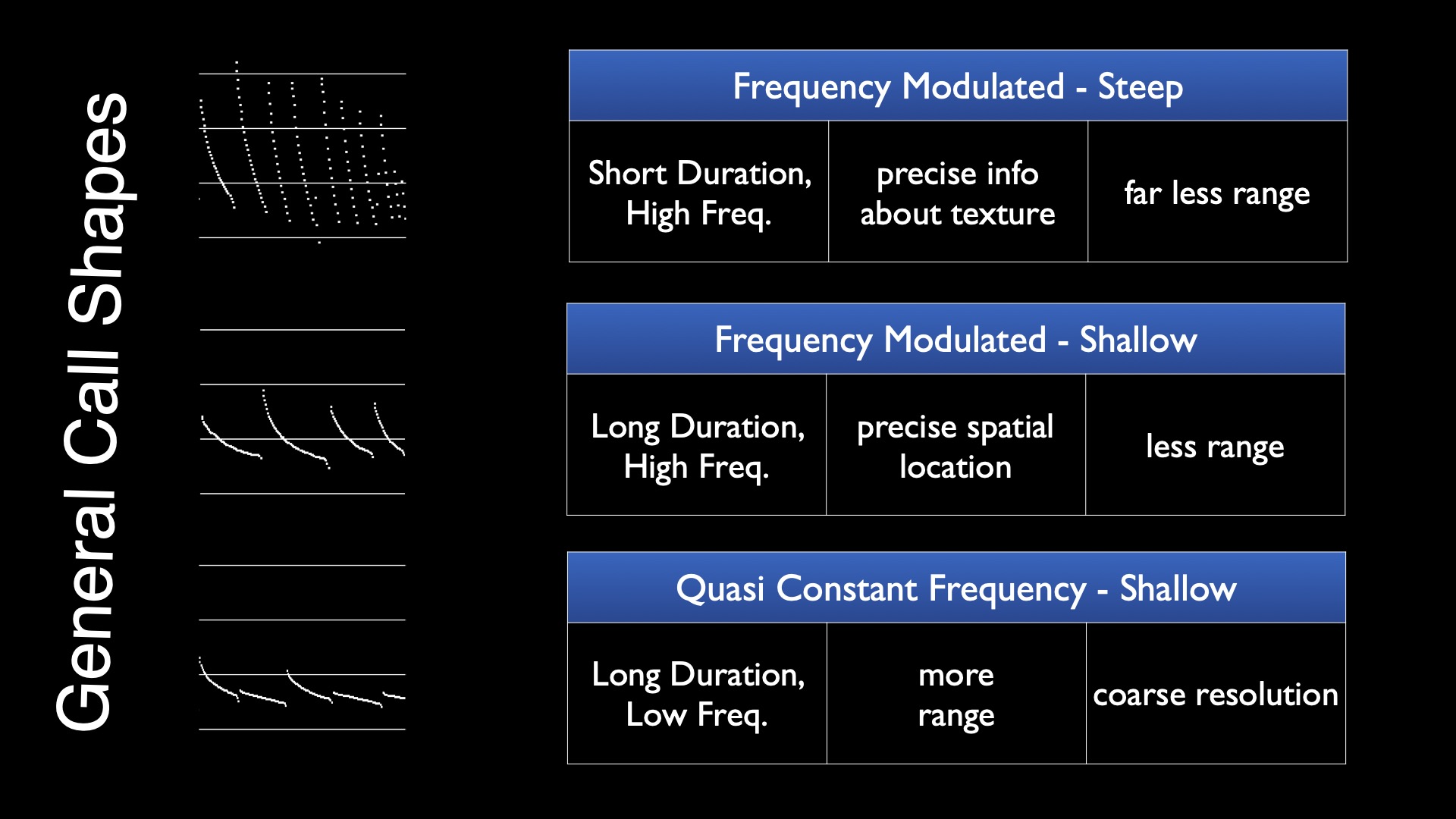

We find bats use different call "shapes" because the shapes are tools that give bats different information about their environment or target. Most species have their preferred frequency range they usually work in. Most will use the same "tools" for searching and especially feeding. Therefore, some bat species are distinct and easy to identify, but others have so much overlap in their toolbox it is impossible for us to tell them apart at this time.

The steep FM calls provide key information about distance to an object, and the most information about its size, shape, and texture. However, the high frequencies do not travel far in air at all.

The shallow QCF calls are concentrated into a narrow frequency band, and the operational range of the call is much greater. It will travel farther and allow a bat to get information about distant objects, at the expense of fine resolution.

Shallow FM calls are simply tradeoffs between range and detail of a target. A bat can switch between any of these calls anytime it likes!

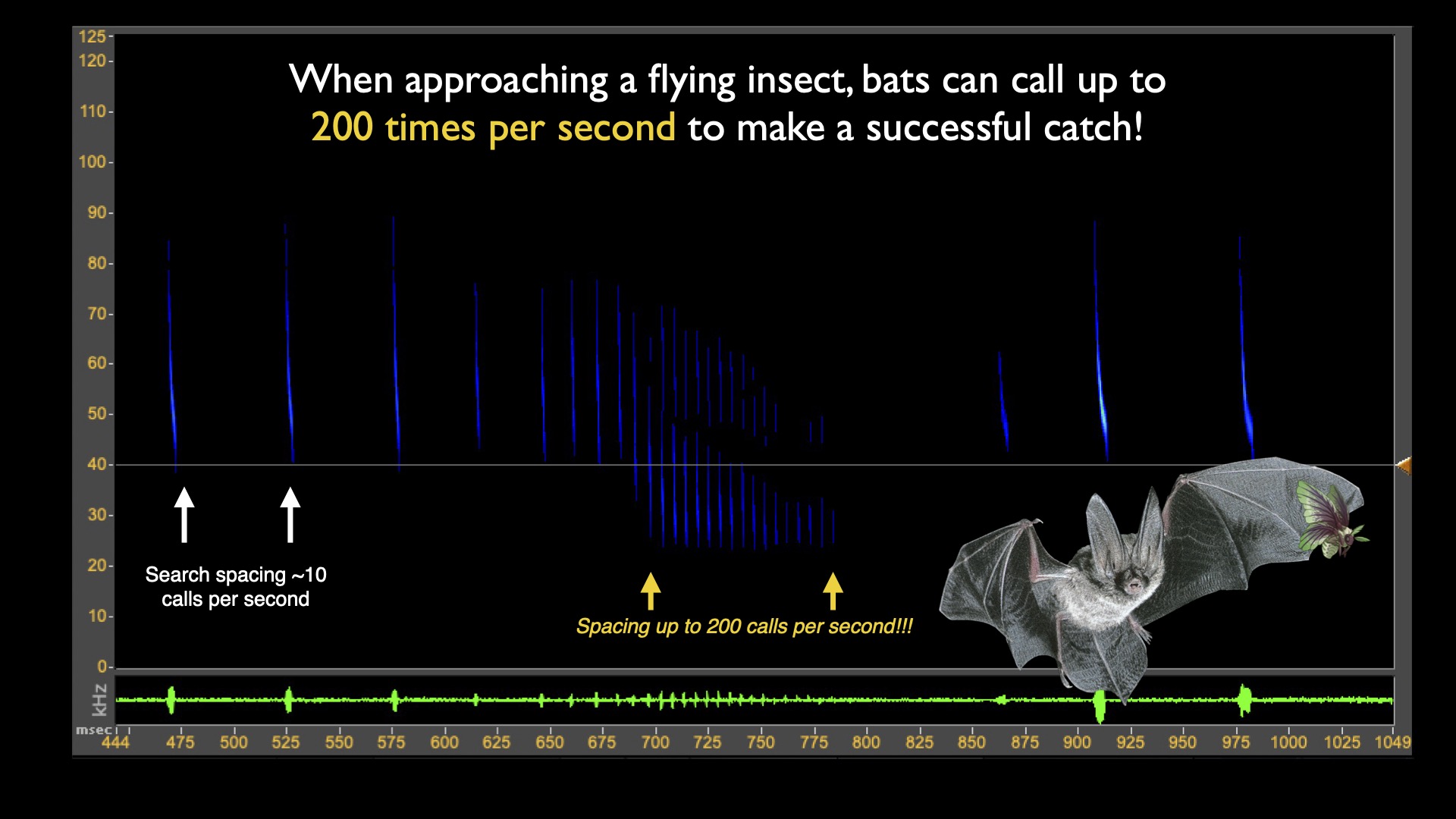

A series of bat calls is called a "sequence". In this recording there are two sequences from different bat species. There is a "high-frequency" bat at the beginning of the recording using typical FM-type calls. The "low-frequency" bat in the second half of the recording is using longer duration, QCF call types.

Bats need to use these very high frequencies because they need to generate very small wavelengths of sound in order to get echoes from very small targets, such as their insect food.

When searching for airborne insects, bats may call up to ~10 times per second. The speed steadily increases the more a bat is interested in something; it must call more frequently to "see" if a target really is something edible. Ultimately the bat will produce calls as fast as 200 per second for a short time to make the final corrections in an attempt to capture prey.

But the insects can hear these loud bats approaching! So they will be taking evasive action and even producing sounds of their own in effort to confuse a bat that is closing in. Some bat species have adapted to whispering, so as to not unnessarilly alert prey to their presence. Others have adapted to literally listening for crawling insects nearby, and will attack prey without using hardly any echolocation at all.